It’s May 1, the traditional day of spring celebrations. In the nineteenth century, May Day also became the day to celebrate workers, who in the cruel era of the Industrial Revolution organized strikes to campaign for the eight-hour workday. “Mayday!” is also the official international distress call issued as an airplane or ship is is going down. Both are chillingly appropriate for this day in 2020.

It’s May 1, the traditional day of spring celebrations. In the nineteenth century, May Day also became the day to celebrate workers, who in the cruel era of the Industrial Revolution organized strikes to campaign for the eight-hour workday. “Mayday!” is also the official international distress call issued as an airplane or ship is is going down. Both are chillingly appropriate for this day in 2020.

As we write on April 30, more than sixty-two thousand have died in America in the last two months. The curve of contagion and death from coronavirus is not flattening. Over a million are infected so far—a million—and probably twice that many aren’t counted in the official statistics. A million, and our political and business leaders seem intent on sending more to the slaughter to keep capitalism running while they can’t even pause to assure testing for everyone. Mayday!

While so many are suffering and out of work, how can we possibly pay any attention to the climate crisis, the destruction of the environment, and the utter incompetence and callousness of our current system?

And yet we must. Our very survival depends on it. Positive change happens not from the top down, but from the bottom up. Trump certainly isn’t going to do it, nor are others in federal government who are also deeply invested in the status quo. TV news gives us nightly reports of hospitals and their heroic staffs begging for equipment just to plug the holes in the dikes of the raging pandemic. Industrial farms are slaughtering and dumping the nation’s livestock, not because there’s anything wrong with the meat but because sick and dying workers can’t process it or get it to stores. The richest country in the world can’t provide equipment to hospitals, or testing to meat processors, because of “the market,” “the supply chain,” competition, profiteering… because of vampire capitalism that makes workers dispensable. May Day!

Let’s shift gears to the local level. Over the last year the KEC has reported on the activities of Washington state’s Board of Natural Resources, a group that oversees the management of the state’s 5.6 million acres of public lands. Established in 1957, the BNR “sets policies to guide how the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) manages our state’s land and resources.” In practice, however, led by the state’s Commissioner of Public Lands, Hilary Franz, the BNR has become a rubber-stamp for timber sales and land swaps to generate money for state operations.[1] Its notion of real policy-making leaves a lot to be desired, and in our view ignores the urgency of climate change. In routine monthly meetings the BNR approves the mowing-down of pristine forest and irreplaceable habitat so as to fund schools and institutions and county services. No one, it seems, is looking at the painfully obvious big picture.

Another issue that defies logic is the spraying of dangerous pesticide poisons on both public and private lands. The KEC has fought since 2018 to educate the public about this folly. Modest gains won through activism turn out to have been temporary. Like the Trump Administration’s gutting of EPA standards while the public wasn’t looking, local governments have recently reversed their positions on the spraying of poison pesticides on roadsides, school grounds, and parks. Kitsap County announced in April that it would resume spraying, and it has already done so, using a stew of chemicals touted as natural (as natural as cancer and coronavirus). They have merely replaced glyphosate by other compounds that are just as toxic. According to the county, it just costs too darn much to control weeds in any other way, and it’s easier to sicken humans and wildlife and kill off all the insects that pollinate the food supply.

We continue to advocate and educate about these suicidal practices because we care. If the pandemic doesn’t kill us, environmental degradation and climate change will. We’ve all learned by now that nature is not an inexhaustible resource. It is finite, and getting finiter by the minute.

But again, how can we care about any of this when thirty million jobs have been lost and our hospitals are filled with the sick and morgues piled with the dead? Surely we must attend to the immediate issues of life and death? Here’s the real news: IT IS ALL CONNECTED by the evils of a system that cares about little but “the economy” (read profit). Repeat: the only way to change things, to value human life and the natural world in which we are guests, is from the bottom up.

So we’ve been thinking and discussing: if we were in charge, what would we suggest to replace spraying with poisons, for example? Would it make sense to give people jobs by putting them to work on maintenance of our roadsides, using mechanical rather than chemical means to control vegetation? Has this mobilization of people by government ever been done before?

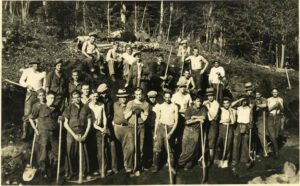

You betcha. In 1932, FDR took America’s political helm during the country’s worst economic crisis, declaring a “government worthy of its name must make a fitting response” to the suffering of the unemployed. He implemented the CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] a little over one month into his presidency as part of his administration’s “New Deal” plan for social and economic progress. The CCC reflected FDR’s deep commitment to environmental conservation. He waxed poetic when lobbying for the its passage, declaring “the forests are the lungs of our land [which] purify our air and give fresh strength to our people.” CCC employees fought forest fires, planted trees, built bridges and campgrounds, cleared and maintained access roads, re-seeded grazing lands and implemented soil-erosion controls. Their labors enhanced infrastructure in national and state parks and forests.

The Thirties also saw the establishment of the Works Progress Administration [WPA], the Tennessee Valley Authority [TVA], the Federal Housing Authority [FHA], and Social Security, for God’s sake. These programs are what allowed the vast majority of Americans to survive the lean and terrible years—not reopening malls, forcing meat workers back into sick plants, and sending out $600 checks to some and multi-millions to Boeing and Ruth’s Chris Steak House.

But we’re living in different times, aren’t we. This government is not going to employ people to maintain roadways as the New Deal did. This government has amply demonstrated that it’s not going to subsidize the costs of ventilators or hospital stays. So again, what social environment existed in the 1930s that allowed for government to actually work for people? And why does our present society not seem to understand or care about what’s in our own interest?

A great recent documentary called Crip Camp traces the development of disability rights in America from the early 1970s to the present.[2] It includes lots of footage of a summer camp in upstate New York where disabled teenagers, many severely affected with everything from autism and birth defects to brain and spinal injuries, frolicked and worked in a kind of disability hippie utopia. The movie follows the lives of a number of those campers as they went on to advocate for the legal protections and autonomy that their camp experience had indicated to them was possible. Through several presidential administrations they weathered the ignorance and arrogance of elected officials, and their persistence eventually led to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, which finally guaranteed physical and educational access and equality to the disabled.

Crip Camp doesn’t dwell on it, but suggests that things came together in serendipitous ways to allow the remarkable story of disability rights to develop. The summer camp’s countercultural values encouraged the creative imagining of a better existence. When disabled demonstrators did a three-week sit-in at the Washington DC offices of Secretary of HHS Joe Califano a few years later, they were sustained by the Black Panthers who brought food and supplies—a beautifully unlikely confluence of oppressed groups demanding their civil and legal rights. One newspaper reporter stuck with them; thanks to a slow national news day, his story of the sit-in was picked up and hit the national news wires, embarrassing government officials into granting key demands. In other words, it was the times, particular individuals, compelling narratives, and sheer coincidence that helped author the ultimate success of this movement.

What can we learn from the two examples of the CCC in the 30s and the disability rights movement of the 70s-90s? It seems as if the times couldn’t be less right, in this historical moment, for our state/county to get the message not to spray poison and cut down “our” forests.[3] The circumstances couldn’t be worse for the balance of power nationally to shift from the privileged rich to the exploited majority, and for the physical and moral health of the nation to be restored. Most urgently, we’re having to practice social distancing and wear masks now, conditions that ironically hamper us more now than did the ravages of polio or degenerative nerve disease in the 1970s for some idealistic young people. How can we possibly gather, plan, debate, influence, and act?

Nevertheless, we can learn something from these examples of past movements. We have to. Mother Earth is clearly communicating that she just can’t put up with us any more in our current social formation. We have to dream a new and better one, dream far beyond the old order. There is no returning to the way things were, because that system has revealed how completely fragile it was and how broken it is now.

On this May Day mayday, we don’t intend to propose solutions, but only questions. How do we mobilize? How do we save the world? How will younger activists, the ones who will inherit it, find inspiration?

by Claudia Gorbman